The Venice Biennale – ‘a bestiary of the imagination’

The alluring theme of the 2013 Venice Biennale is ‘Il Palazzo Enciclopedico’, an imaginary museum that holds all human knowledge. Universal knowledge is so enticing, isn’t it? We have the Internet, we can ‘know’ anything; it’s all at our fingertips. But this exhibition ignores social media, television and popular culture. It is about creativity, the human imagination; it ventures into the artists’ worlds and explores the way images organise knowledge and shape our experiences. Massimiliano Gioni, the exhibition’s curator, says “Like the theatres of memory devised in the 16th century by Venetian philosopher Giulio Camillo–mental cathedrals invented to order knowledge through pictures and magical associations–the exhibition “Encyclopedic Palace” will compile a cartography of our image-world, composing a bestiary of the imagination.”

We wander freely amongst these peculiar, enthralling objects–a vast cabinet of curiosities, almost infinite in scope–without any pressure to think in this way or that; it is an unfettered journey of thought, an adventure for the imagination.

For me it was also an adventure across Europe to an apartment in a lovely, decaying Venetian palace, the perfect place to brood on the day’s horde of images. The owners seemed to be fighting a perpetual battle to keep the buildings habitable but our huge old battered apartment was a beautifully relaxing place to return to for an icy G&T, to rest the aching feet and cool the sun-burned shoulders. It was on the top floor with views down to a sleepy canal on one side and a vast terrace, almost the size of a tennis court, on the other with scuttling lizards, views of a tumble of terracotta rooftops and all so quiet, just the lap of water and the squawk of gulls.

The Biennale comprises two main sites: Arsenale, a central exhibition space in the old armories and extending into a massive expanse of dockland warehouses, and Giardini, which comprises a central pavilion and thirty or so smaller country-specific pavilions all set in a public garden. Another 35 countries exhibit in palaces, hotels and random buildings across Venice and a further 47 collateral exhibitions are also spread across the city. In fact there are even more than that, because our ‘palace’ was exhibiting interesting work: The Second Sex by Joseph Badalov, a personal exploration of ‘other women’ who challenged gender stereotypes in USSR. So, in fact, even though Venice is small, there is far too much to get around in a week.

It’s a great opportunity to snoop around places that are not usually open to the public: the ancient stone music conservatoire, a room lined by oak cabinets on the third floor of the Academy of Science, a palace converted into luxury apartments, the telecom’s offices in an old convent, loads of palaces and hotels. And nearly all these are free. An exception, at three euros, is the Norwegian exhibition Beware of the Holy Whore, which includes an intriguing collection of Munch and Dirty Young Loose, a weirdly, fascinating film written and directed by Lene Berg that reminded me strangely of the sort of disconnection between viewer and characters and between characters that I’ve noticed in Wallander. The brilliant Korean exhibition, Who is Alice?, is a fantastical group of works set in a series of rooms tucked away in an old house near the Rialto Bridge. So, apart from visiting Arsenale and Giardini, it’s best to wander and, like Alice, see what you stumble upon.

The first thing you see in Arsenale is an architect’s model in plaster of a towering skyscraper. In 1955, Italian-American self-taught artist, Marino Auriti, after retiring from his job as a motor mechanic, filed a design with the U.S. Patent office depicting his Palazzo Enciclopedico. This imaginary museum would house all knowledge, bringing together the greatest discoveries of the human race, from the wheel to the satellite.

Massimiliano Gioni is the curator of the Biennale’s version of this concept which is about the desire to see and know everything to the point of obsession. So many of us can sympathise with that. Perhaps it’s something we try to keep to ourselves, this obsession with the right word or exactly the right image, the obsession with research that stops us actually getting down to writing. Knowledge is so interesting. Ideas are so absorbing. What do you think I’m doing here? Depressingly, Auriti’s museum was never built but his building is the image that symbolises Gioni’s concept.

The fact that Auriti was a self-taught artist is also significant to the Biennale. Gioni has said he is questioning the identity of the art object:

“Blurring the line between professional artists and amateurs, outsiders and insiders, the exhibition takes an anthropological approach to the study of images, focusing in particular on the realms of the imaginary and the functions of the imagination. What room is left for internal images—for dreams, hallucinations and visions—in an era besieged by external ones? And what is the point of creating an image of the world when the world itself has become increasingly like an image?”

The insider/outsider debate is an interesting one and I wonder to what extent it might apply to writers.

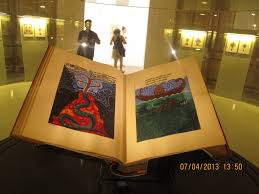

At the entrance to Giardini we are given our human guides, the men who will accompany us on the journey. Who better than two men who built their lives on dreams? Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and André Breton, the French poet and spokesman for the Surrealists. On display is Jung’s famous ‘Red Book’ in which he recorded his visions, hallucinations and dreams, his ‘horrible confrontation with the subconscious’. The Red Book is displayed in a glass case and the darkened room is surrounded by copies of the illuminated illustrations.

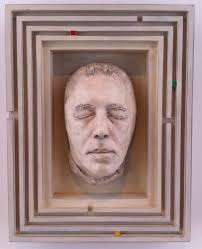

A little further on, we see René Iché’s ghostly plaster-cast mask of André Breton. Breton’s eyes are closed and yet he’s somehow wide-awake, very present–he wasn’t dead when Iché made the mask–you expect the eyes to flash open and the face to grimace and yowl at you.

Just behind the head of Breton is a vast bright white room lined with the chalk on blackboard drawings of Rudolf Steiner, the cultural philosopher and founder of anthroposophy–the exhibition’s logo is taken from his drawings. Steiner’s spiritual science sought to provide a connection between the cognitive path of Western philosophy and the inner and spiritual needs of the human being and his architectural work culminated in the building of the Goetheanum, a cultural centre to house all the arts, another kind of encyclopedic palace.

Breton’s spirit is everywhere. He is quoted: “to reduce the imagination to a sense of slavery, is to betray all sense of justice within oneself”. The words, ‘phantasmagorical’ and ‘palimpsest’ crop up time and time again, the work of Borges is also much bandied and quoted . Just after we have met the head of Breton we come across a video of his apartment in Ed Atkin’s brilliant work The Trick Brain. With a wonderfully enigmatic script spoken and subtitled, Atkins has adapted a reel of film shot in André Breton’s Parisian flat at 42, Rue Fontaine, before its contents were auctioned off. His introduction to the work is here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RiDLzDr0KKY

The camera slow-pans through Breton’s disturbing collection of exotic curiosities–tribal fetish objects, Surrealist paintings, interesting old junk. It’s a magic place, haunted and it’s crammed. I’m not averse to clutter believe you me but I don’t know how he moved around in there. Atkins’ script is intriguing; it releases the objects, gives them another life or perhaps he gives them death and his narrative possesses its own music. It can be read here:http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/downloads/testing/The_Trick_Brain_Ed_Atkins.pdf

Although Auriti’s vision was utopian, dystopian work is in abundance, dancing skeletons feature highly. I was astounded by the incredible work in the Chinese pavilion—the dystopian energy drags you, inwardly shrieking, from one startling image to the next.

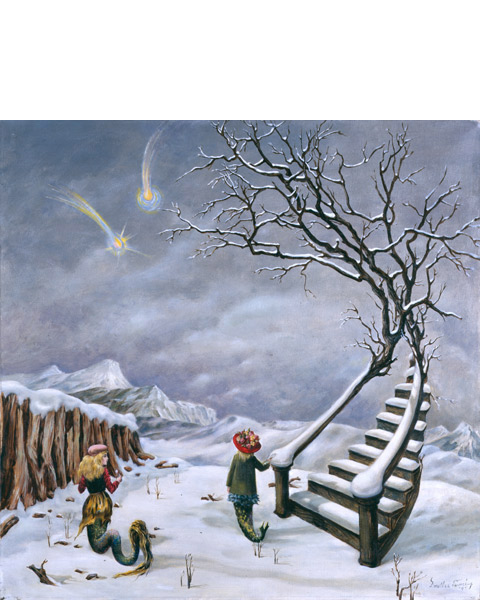

So many works struck a chord with me and those I can easily bring to mind right now that are from the main exhibitions include Dorothea Tanning’s Self-portrait and The Truth About Comets:

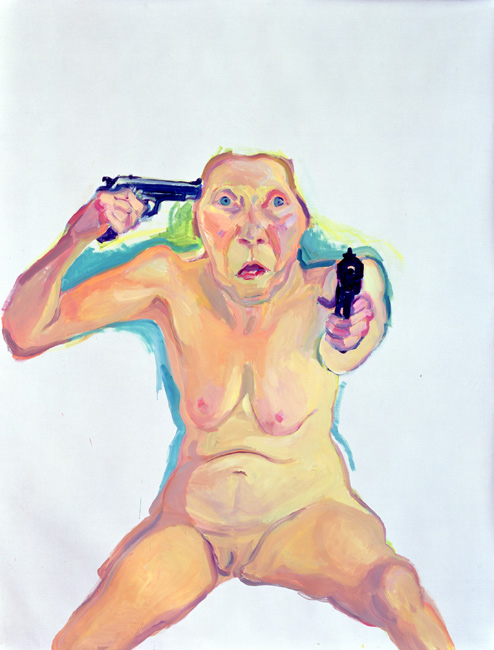

Thierry de Cordier’s sea paintings, Maria Lassnig’s self-portrait You or Me:

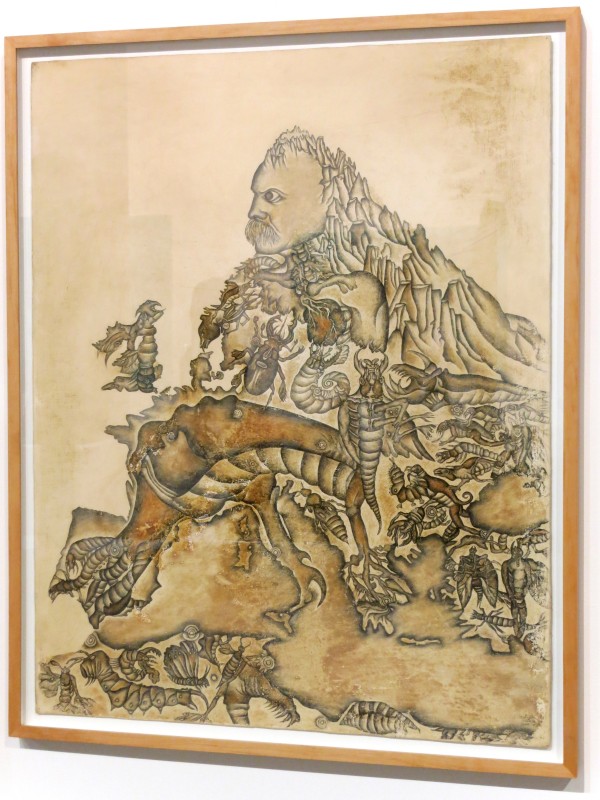

Yüksel Arslan’s heads and land masses made of creatures,

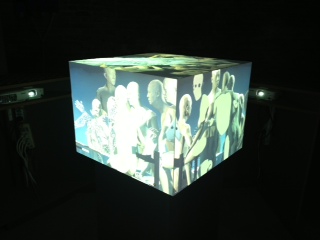

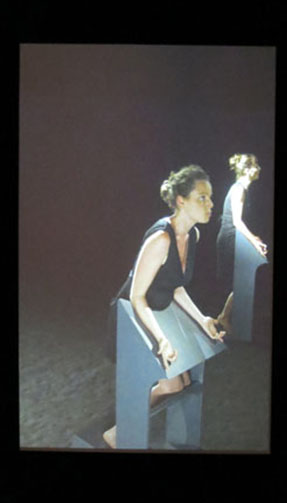

Victor Alimpiev’s film of two women singing simultaneously—one in future tense the other in present:

Aurélien Froment has a woman mnemonist dramatically declaiming Giulio Camillo’s 15th-century Theatre of Memory,

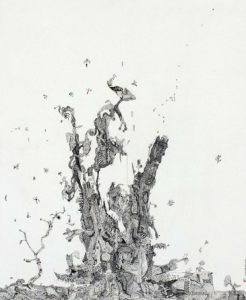

Lin Xue’s intricate ink ecosystems drawn with a twig:

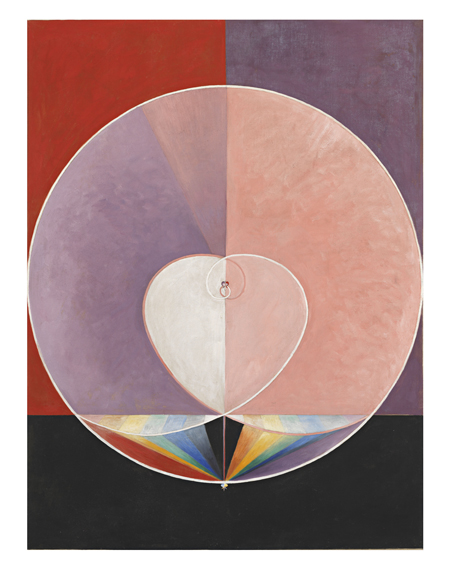

Hito Steyerl’s How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/may/31/hito-steyerl-how-not-to-be-seen/, an instructional video on how to remain invisible in an age of image proliferation (one of which is to become a woman over fifty) and the weird metaphysical visions of Hilma af Klint.

One of the most wondrous performance-pieces I’ve ever seen is the work of Icelandic artist, Ragnar Kjartansson. A small Viking -type sailing boat that has been converted from a bar (the boat is named Hangover) is moored in a huge, covered, colonnaded wharf – every now and then a six-piece brass band climbs aboard, the captain sets sail and the boat moves sedately off and the band starts playing this beautiful, Sibelius-type music commissioned especially for the installation. The sound drifts on the wind and through the stone colonnades, changing pitch as the boat tacks slowly out into the lagoon, just a few meters, and the captain turns the boat and it sails into the adjoining wharf, turns round–all very unhurried, whilst the band keeps playing this beautiful mountainous music. I always think there’s something strange about music on the wind, the way rhythm is batted about and pitch is tinkered up and down, nature adjusting art. Here it is as if the music is captured by the sail, fills the water until it becomes solid with sound as the boat tacks back into the lagoon and returns to the wharf. Then they anchor and the band stops. Odd, quirky, hilarious in a way, but tremendously powerful. Hats off to the bandsmen, just think–this installation started in June and continues into late November and they have to keep playing the same short piece. I actually barged in on them by mistake while they were having a tea break in a nearby warehouse (I thought it was another installation); the trumpeter was still playing–he couldn’t seem to stop.

-type sailing boat that has been converted from a bar (the boat is named Hangover) is moored in a huge, covered, colonnaded wharf – every now and then a six-piece brass band climbs aboard, the captain sets sail and the boat moves sedately off and the band starts playing this beautiful, Sibelius-type music commissioned especially for the installation. The sound drifts on the wind and through the stone colonnades, changing pitch as the boat tacks slowly out into the lagoon, just a few meters, and the captain turns the boat and it sails into the adjoining wharf, turns round–all very unhurried, whilst the band keeps playing this beautiful mountainous music. I always think there’s something strange about music on the wind, the way rhythm is batted about and pitch is tinkered up and down, nature adjusting art. Here it is as if the music is captured by the sail, fills the water until it becomes solid with sound as the boat tacks back into the lagoon and returns to the wharf. Then they anchor and the band stops. Odd, quirky, hilarious in a way, but tremendously powerful. Hats off to the bandsmen, just think–this installation started in June and continues into late November and they have to keep playing the same short piece. I actually barged in on them by mistake while they were having a tea break in a nearby warehouse (I thought it was another installation); the trumpeter was still playing–he couldn’t seem to stop.

In fact so much artistic brilliance is present I can’t possibly describe it all here. Exploring the work of such a vast number  of contemporary artists leads one to a luxuriant spread of surprises. I hadn’t expected to find such an adventure of the imagination. It is dystopian in places and yet in totality so optimistic. I love that. Creativity is in essence optimistic. No escaping that I think. Depression doesn’t help us create but creativity does sometimes negate depression, and maybe they feed off each other. In Venice it was as if I’d had a shock straight to the brain, I was flitting here and there, randomly mixing artists and images, jotting crazy notions and ideas in my little green notebook. I’m nourished and I’m powered up creatively. I’ve booked for 2015. Can’t wait!

of contemporary artists leads one to a luxuriant spread of surprises. I hadn’t expected to find such an adventure of the imagination. It is dystopian in places and yet in totality so optimistic. I love that. Creativity is in essence optimistic. No escaping that I think. Depression doesn’t help us create but creativity does sometimes negate depression, and maybe they feed off each other. In Venice it was as if I’d had a shock straight to the brain, I was flitting here and there, randomly mixing artists and images, jotting crazy notions and ideas in my little green notebook. I’m nourished and I’m powered up creatively. I’ve booked for 2015. Can’t wait!