I’ve just finished…The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Dorset landscape has a mystical and deeply private beauty; there is a sense that things are going on, and have been doing so for many centuries, hidden things that are too private to talk about. Hardy evokes this in his writing.

The Dorset landscape has a mystical and deeply private beauty; there is a sense that things are going on, and have been doing so for many centuries, hidden things that are too private to talk about. Hardy evokes this in his writing.

I’ve just finished reading The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy. Casterbridge is, of course, Hardy’s name for Dorchester. Although I was born in Hampshire, the government changed the county boundaries and consequently I spent my youth in Dorset. The landscape is the most intimate in the country, full of natural amphitheatres, secret valleys and ancient earthworks. It has a mystical and deeply private beauty and there is a sense that things are going on, and have been doing so for many centuries, hidden things that are too private to talk about. Hardy evokes this in his writing.

Hardy was born in Dorset in 1840 and died there in 1928. His father was a stonemason and his mother, who was well-read, ensured that he had a good education in Dorchester schools. He studied architecture at Kings College London. Hardy hated London. He was acutely aware of class division and found London society, particularly the sense of his own social inferiority, intolerable. It was not until the success of ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’ in 1874, that he was able to give up architecture and return to the West Country to write full time. In the same year, he married Emma Gifford, she was his great love and although they became estranged later, she remained his own tragic passion. After her death in 1912, Hardy fell into a trauma. Soon after, he married his secretary, Florence Dugdale, 39 years his junior, (shades of Dostoevsky here) but Emma remained his lifelong passion and obsession.

and his mother, who was well-read, ensured that he had a good education in Dorchester schools. He studied architecture at Kings College London. Hardy hated London. He was acutely aware of class division and found London society, particularly the sense of his own social inferiority, intolerable. It was not until the success of ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’ in 1874, that he was able to give up architecture and return to the West Country to write full time. In the same year, he married Emma Gifford, she was his great love and although they became estranged later, she remained his own tragic passion. After her death in 1912, Hardy fell into a trauma. Soon after, he married his secretary, Florence Dugdale, 39 years his junior, (shades of Dostoevsky here) but Emma remained his lifelong passion and obsession.

Hardy’s characters are t ragic. They struggle against prejudice and bigotry, fighting against their passions and social circumstances. ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’ begins at a country fair outside Casterbridge. The troubled Michael Henchard is looking for work but gets drunk and auctions off his wife, Susan, and baby daughter, Elizabeth-Jane, to a sailor, Mr Newson, for five guineas. Henchard regrets this the next morning and swears to remain sober for the next 21 years. Henchard becomes a successful and well-respected grain merchant known for his sobriety and violent temper. No one likes him very much. Henchard allows people to think that Susan is dead. Whilst travelling to Jersey on business, Henchard begins a sexual relationship with Lucetta but effectively abandons her on his return to Casterbridge. He has built a successful life to outward appearances but inside he is tormented, having imprisoned himself within a fortress of deceit and appalling behaviour. Eighteen years later, when Susan and Elizabeth-Jane turn up in Casterbridge,Henchard’s fortunes begin the inevitable decline. He loses all his friends, his

ragic. They struggle against prejudice and bigotry, fighting against their passions and social circumstances. ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’ begins at a country fair outside Casterbridge. The troubled Michael Henchard is looking for work but gets drunk and auctions off his wife, Susan, and baby daughter, Elizabeth-Jane, to a sailor, Mr Newson, for five guineas. Henchard regrets this the next morning and swears to remain sober for the next 21 years. Henchard becomes a successful and well-respected grain merchant known for his sobriety and violent temper. No one likes him very much. Henchard allows people to think that Susan is dead. Whilst travelling to Jersey on business, Henchard begins a sexual relationship with Lucetta but effectively abandons her on his return to Casterbridge. He has built a successful life to outward appearances but inside he is tormented, having imprisoned himself within a fortress of deceit and appalling behaviour. Eighteen years later, when Susan and Elizabeth-Jane turn up in Casterbridge,Henchard’s fortunes begin the inevitable decline. He loses all his friends, his  fortune, the respect of his community and despises himself, hating everyone and everything as he becomes increasingly entangled in the web of his own lies and self-hatred.

fortune, the respect of his community and despises himself, hating everyone and everything as he becomes increasingly entangled in the web of his own lies and self-hatred.

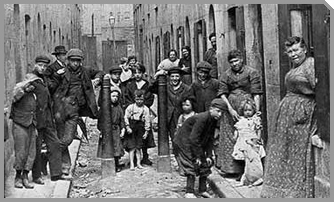

It’s absolutely gripping and moving. I love the way he describes everything in terms of Nature. The birds and the smell of the hay and how it’s turning. You can breathe the dusty grain, suffer the tiring walks along muddy lanes, feel the expectation and defeat at the crossroads. As I read, I pictured the pubs in Dorchester and Hardy’s ‘Roman amphitheatre’ (the Neolithic earthworks pictured above) known as Maumsbury Rings near the town centre that was used in the 17th and 18th centuries for executions. It’s such a brilliant read and utter genius how Hardy sets you up and everything seems to be working out brilliantly for everyone for about the first third of the book, then things turn sour and Hardy piles the misery onto the reader so you go through every torment with Michael Henchard. You sympathise with him with all your heart and yet you despise his uncompromising idiocy. You want to whisper in his ear, take his hand (if you dare) tell him no, don’t do that, don’t go down there, have courage.

Hardy is a social realist. He was 30 when Dickens died and was, without doubt, influenced by Dickens’ realism and attitude to class but whereas Dickens frequently caricatures or pokes fun at poorer people and social outcasts, this does not happen in Hardy’s work. Perhaps Hardy’s work has more in common with that of Balzac where great passion and mad love  cross the boundaries of social class or Dostoevsky’s social realism where poverty and hardship drive the protagonist to enormous feats of self-deception moving them to take great personal risks and to perform insane acts of self-destruction. Interestingly, Hardy is an exact contemporary of Henry James. Although writing novels of social conscience, James’ world could not be more different. James, of course, was born into a wealthy American family and was well-travelled and well-connected.

cross the boundaries of social class or Dostoevsky’s social realism where poverty and hardship drive the protagonist to enormous feats of self-deception moving them to take great personal risks and to perform insane acts of self-destruction. Interestingly, Hardy is an exact contemporary of Henry James. Although writing novels of social conscience, James’ world could not be more different. James, of course, was born into a wealthy American family and was well-travelled and well-connected.

I’ve been meaning, for a long time to reread the work of Hardy and take a camping trip down to Dorset, it’s only an hour’s drive from my house. I’d like to read while leaning over Tess’ woolbridge or the cobb at Lyme Regis or sit in one of the Dorchester pubs with a book or search out that amphitheatre. I wonder if they still make furmity. I know they do a meaty range of ciders down there…

long time to reread the work of Hardy and take a camping trip down to Dorset, it’s only an hour’s drive from my house. I’d like to read while leaning over Tess’ woolbridge or the cobb at Lyme Regis or sit in one of the Dorchester pubs with a book or search out that amphitheatre. I wonder if they still make furmity. I know they do a meaty range of ciders down there…

If you’re interested in Hardy, You might like my post on ‘The Return of the Native’.

Or, if you’re interested in 19th century literature you might be interested in my trip to St Petersburg and my visit to Dostoevsky’s flat.