The Street of Crocodiles

If you haven’t read ‘The Street of Crocodiles’ by Bruno Schulz, head on to Over the Red Line, where my review is up. It will give you a taste of what to expect.

Schulz is an extraordinary writer and whilst I’m reading the mostly ‘indoor’ life of these stories, I can’t help feeling that I’m also inhabiting, and even directly experiencing, the incredible riches of Schulz’s imagination. They’re powerful. The Quay brothers made an animated film of ‘Street of Crocodiles’ in the eighties. It’s here, and although intense and fantastical, it doesn’t demonstrate the sensuousness of Schulz’s writing. I won’t go on about it because it’s all in the review.

Over the Red Line asked me to write the review because my very short story ‘Gloves of Gdansk’, which is a sort of homage to Bruno Schulz, won the Litro Poland/Schulz prize. It’s here if you want a quick read, and was displayed on the London underground for a while, a fact that fills me with an inordinate degree of pride!

I’ve pasted a draft of my article below in case anyone’s interested in Schulz but do foray over via the link to glean lots of quirky writing and reading stuff from Over the Red Line.

Originally called Cinnamon Shops, you taste these stories on your tongue, you’re lured by their richness of language, and before you know it you’re hooked by their logic, your mind entangled in Schulz’s nightmarish mythology.

…the shiny pink cherries full of juice under their transparent skins, the mysterious black morellos that smelled so much better than they tasted, apricots in whose golden pulp lay the core of long afternoons. And next to that pure poetry of fruit, she unloaded sides of meat with their keyboard of ribs swollen with energy and strength.

And that’s why I love Schulz, the language, intensity, the philosophy and the disturbing visionary world but I also love him because of his background, and the fact that, in spite of every possible difficulty, he kept writing. He must be the ultimate writer’s writer.

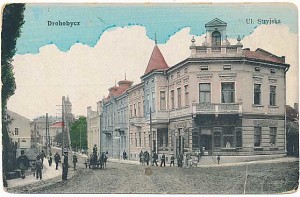

Bruno Schulz is unusual in that he did not travel. He spent his whole life in Drohobycz, Poland (now in Ukraine) the same town where he based Street of Crocodiles, and that forms the great Labyrinth of his mythology. He took only two forays out of Drohobycz, one short trip to Stockholm and three weeks in Paris. For all his adult life, he worked as an art teacher in the local Gymnasium. He wrote during the school holidays, and in the evenings when he wasn’t marking homework. His artwork, including many erotic drawings of the ladies of Drohobycz, was exhibited and given good reviews (although some of the women complained), and as a result he was promoted at his school. He never married. Both eroticism and comedy play a big role in his fiction.

Adela’s outstretched slipper trembled slightly and shone like a serpent’s tongue. My father rose slowly, still looking down, took a step forward like an automaton, and fell to his knees.

I could not resist the impression, when looking at the sleeping condor, that I was in the presence of a mummy – a dried-out, shrunken mummy of my father. I believe that even my mother noticed this strange resemblance, although we never discussed the subject. It is significant that the condor used my father’s chamber pot.

The Street of Crocodiles’ draws on the Drohobycz of Schulz’s childhood and, turns it into a fantastic world. Father is a crucial character in this mythology who holds great power and Adela, the servant, is the demonic object of desire. At one point Father is lying in bed:

He felt without looking, how the pullulating jungle of wallpaper filled with whispers, lisping and hissing, closed in around him.

And a few pages on:

About that time, we noticed that Father began to shrink from day to day, like a nut drying inside its shell.

Historically and personally, Schulz was a writer thwarted by circumstance. In 1892, when he was born, Drohobych was in the hands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, after WW1 it was Polish, briefly Soviet, and then at his death part of Nazi Germany. All this meant constant upheaval and Schulz found himself trapped by the limited financial rewards of his teaching job. He received no royalties from his stories even though his work received some acclaim and he complained that he never had enough time to write, but he was never able to leave his job because he had to make a living. Even the decision to go to Paris was weighed up against the need to buy a new sofa. Schulz dreamed of winning the State lottery so he could write.

As we walk with the young boy and his mother round the labyrinthine streets of Drohobycz to their apartment above the haberdashers he tells us:

It seemed as if whole generations of summer days, like patient stonemasons cleaning the mildewed plaster from old facades, had removed the deceptive varnish revealing more and more clearly the true face of the houses, the features that fate had given them and life had shaped for them from the inside.

Because what goes on in the inside is a mystery, always, isn’t it?

It is from this frustration, that Schulz created this elaborate inward mythology. His stories don’t apparently reflect political life but he dazzles us with everyday details, the things we all recognize, and then, blink, it all changes and he twists reality but without any attempt to shock. His stories are intense and extreme, unlike real life, but real life is still the foundation. As he says when talking about great moments in life:

they are trying to occur, they are checking whether the ground of reality can carry them.

Schulz’s output is small: The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass are his only fictional work. His novel, Messiah, has never been found and it’s likely he never finished, or perhaps never started it. Schulz was killed by a Gestapo officer in the streets of Drohobych in 1941, he was planning to escape that very evening.